Zoe Zucker is a junior student at Boston University. She interned at IDIE for a semester in 2025, where she researched on intersectionality during Australia’s COVID-19 response. Read more of her work below

The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a need to reexamine the healthcare system and how minority groups fair during a public health crisis. Individuals experiencing disadvantage across multiple dimensions, such as through housing insecurity in addition to societal racism, endure crises differently, in ways that are not properly dealt with and treated. Current support services and data collection tools are not intersectional, and this prevents the development of appropriate and effective solutions.

Intersectionality is often unexplored in the realm of healthcare, to the detriment of individuals with needs that are more complex than the system tends to frame them to be. Population groups that identify with multiple groups, such as migrants, First Nations peoples, and those dealing with housing insecurity, are often ignored in healthcare, which traditionally seeks to categorize people for the means of effective and easy treatment. As a result, it fails patients and leaves them lacking quality care instead. This is especially the case in public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Australia’s minority communities, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (henceforth First Nations peoples) and migrants, have been and are disproportionately affected by public health crises. As of 2024, 31.5% of Australia’s population was born outside of Australia, and as of 2021, 3.8% is First Nations, and 48% have a parent born overseas (1). Many from these backgrounds are at an increased risk of contracting viruses such as COVID-19 (2). This results from discrimination in conjunction with structural factors such as higher likelihoods to live in high-density households, or to work in insecure, high-risk employment (3–10). In a 2022 public housing survey by the Australian government, 9.5% of all First Nations households were living in overcrowded dwellings, compared to only 4.5% of all households. Bias, including racism, shapes social determinants of health and is a driver of adverse health outcomes in minorities. Existing inequalities and a lack of inclusion contribute to continued distrust in the health care system and the government. Systemic inequalities in job security, access to paid sick leave, and affordable housing and healthcare disproportionately affect these groups, contributing to housing insecurity. The employment rate remains considerably lower among First Nations peoples than non-First Nations Australians (56% compared with 78%) (11).

The Australian government defines homelessness not solely as rough sleeping. It identifies people experiencing homelessness as those in supported accommodation– commonly used by refugees or those in a crisis– as well as those living in severely crowded dwellings, with the latter representing 39.1% of those counted as homeless by the 2021 Census (12). Minority groups, including First Nations peoples and migrants, are more likely to live in overcrowded and under-resourced communities and to work in lower paid jobs, many of which carry a high risk of exposure to COVID-19. The main responses from Australian governments were targeted towards those sleeping rough, despite risks being more significant for individuals living in overcrowded settings (3).

Due to these inequities, there were disparities in vaccine coverage and pandemic preparedness among housing insecure, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD), and First Nations communities. Prior to the pandemic, there were no specific public health emergency plans for CALD communities in place (3). The COVID‑19 pandemic exposed pre-existing gaps in planning and engagement with such groups who require additional support, yet face governmental neglect. When people do not feel represented or heard in healthcare, especially against a backdrop of colonialism and discrimination, engagement and trust can be lost. The status quo is built upon knowledge and assumptions about the majority population in an area. Intersectionality amplifies this issue, expanding dimensions of hurt, and neglecting already fragile relationships between systems and those that they are tasked to represent.

The failure to adequately plan for the differing impacts of COVID-19 among and across different Australian populations enabled the virus to spread faster and wider. However, little is known about the challenges faced by intersectional communities during COVID-19. This report aims to analyze the importance of applying an intersectional lens to healthcare, specifically as it pertains to health gaps among homeless and minority populations during public health crises, specifically within the COVID-19 context.

Housing and Homelessness Services

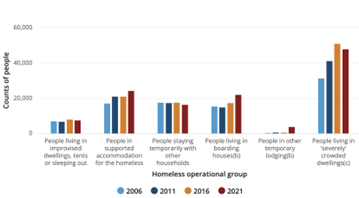

In Australia, services for people who are homeless and at-risk for homelessness are predominantly provided by specialist homelessness services (SHS), which receive state government funding. Spending by states and territories on homelessness services increased by 21.9% from 2018-19 to 2020-21, tied to a broader increase in government spending on social services during COVID-19. Funding was largely aimed towards rough sleepers, despite severely overcrowded dwellings being the most common and one of the fastest growing types of homelessness, which, as of 2021, has risen by 52% since 2006 (13). Consultation and collaboration between the government and homelessness and housing sectors were too slow at the start of the pandemic, particularly in relation to policy, impacting effectiveness and resource allocation. Related services were under-resourced during COVID-19, and there was no surge workforce or workforce plan in place (3).

FIGURE 1: Australian Homelessness Population Makeup (12)

Support was withdrawn too quickly and without proper consideration for the impact on people experiencing housing insecurity. With the ease of lockdown orders and the gradual removal of transmission protections in late 2021 came a reduction in public health measures for assisting homeless Australians. In many cases, this left people in a similar or even worse position to before the pandemic. Risks were especially significant for those in overcrowded settings, which greatly increase the chances of disease transmission, and disproportionately impact low-income individuals and recent immigrants (3). A 2020 report by the United Nations found overcrowded housing, not density, to be the main factor contributing to the spread of COVID-19 (14,15).

In Australia, rates of housing insecurity and demand for homelessness services are only increasing. This is due to a cost-of-living crisis in the nation and a critical shortage of affordable housing. In post-pandemic years, this increase in funding has slowed dramatically, only growing by 0.6% from 2021-22 to 2022-23 (13), not keeping to pace with the growth in homelessness. The more Australians living in insecure or overcrowded housing during the next public health crisis, the more difficult the response will be.

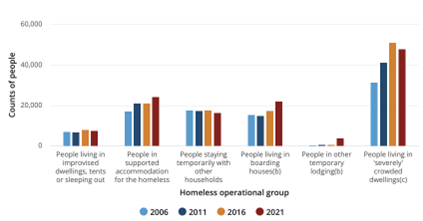

Homelessness Among CALD and First Nations Peoples

Inequities in the housing system are especially felt by under-served communities, particularly CALD and First Nations peoples, in specific, migrants (16). First Nations Australians are over-represented among those counted as homeless in the country. In the 2021 census, this figure amounted to roughly 24,930 individuals. Despite making up only 3.8% of the total population, 20.4% of all people experiencing homelessness are First Nations, with 60.0% of this category living in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings, according to the census’ standard (17).

FIGURE 2: Homelessness Among First Nations peoples (12)

Populations residing in different areas experience different barriers to accessing proper resources, such as appropriate and equitable healthcare. There are more than 150 remote First Nations communities in Australia, where there is usually only one primary care clinic staffed by a small team often solely supported by fly-in-fly-out doctors and specialists. Roughly 20% of First Nations people live in the remote areas of Australia, with 41.4% living in inadequate housing conditions. Individuals often have lower incomes and educational attainment and poorer access to health services, yet pay higher prices for goods and services, making remote living a significant risk factor for homelessness (18,19). Those living in the more remote areas of Australia have 1.4 times the burden of disease when compared with the general population living in major cities and higher rates of homelessness (20). In major cities, similar inequities persist, with 15.5% of First Nations Australians living in unsafe or unfit housing conditions, compared to 6.1% of non-First Nations Australians. Overcrowding and housing shortages in these settings make physical distancing virtually impossible and increase the risk of rapid transmission (5,7,21).

COVID-19 worsened risk factors for homelessness, such as unemployment and housing stress, especially so for already disadvantaged minorities such as migrants (22). During the start of the pandemic, there were increases in social security payments for those on low or no income, along with rental subsidies and restrictions on evictions. Yet these services were not provided to non-citizens, with the lack of financial support during the pandemic undermining social cohesion and exacerbating a sense of rejection and abandonment felt by many. Migrants and international students were excluded from government economic support, with programs like JobKeeper leaving out casual and migrant workers (3,23). As a result, immigrants were especially impacted by the economic constraints brought on by the pandemic, increasing the likelihood for homelessness.

The issue of housing insecurity for migrants is not new. In the 2016 census, 15% of those counted as homeless were born overseas and had arrived in the country in the last 5 years. Of those, the rate of living in severely crowded dwellings had nearly doubled since 2021. Despite this, 87% of SHS clients in 2020-21 were born in Australia (24,25). SHS networks and community-led assistance programs can help contribute to such efforts and address gaps in those receiving support.

The Impact of Housing on Health

There is a clear link between housing and health outcomes demonstrated in various studies (3,4,26, 30). In one conducted in 2023, 24% of social housing tenants reported five or more health factors (such as asthma and hypertension) compared to 3-6% of people in other housing types (27). Secure housing is a critical determinant of outcome in the face of a public health emergency. Social determinants of health, including cultural barriers, socioeconomic status, poor and overcrowded housing, high-risk occupations, and higher burden of comorbidities, are all particularly present within minority communities. Minority and housing insecure individuals are at risk of missing out on key health messages. Barriers to accessing information include gaps in language translation, media and health literacy, and a lack of stable addresses or communication pathways (28). Additionally, stigma and discrimination can lead individuals to avoid healthcare settings.

Greater barriers to accessing or receiving health services among such communities are largely ignored and have rarely been rectified. Many of the hardest hit areas during the pandemic, like Sydney’s south-west, were areas with high migrant populations (16,29). Minority communities, due to inequities in resource allocation and circumstance, often experience poorer living conditions, marked by overcrowding, disproportionately large households, and reduced access to public open space. Structural/institutional racism adversely impacts health by isolating communities with poor quality housing and neighborhood environments and cementing these conditions. Residential segregation further entrenches differences across ethnic divides in socioeconomic status, making escaping such circumstances all the more difficult. Such factors cluster together psychological and physical stressors, which when combined with reduced access to resources, lead to worse health outcomes (30).

Some members of CALD and First Nations communities experienced worsening housing situations or increased risk of homelessness as a result of the pandemic (3). In any public health emergency, First Nations peoples face higher risks (6,31). In the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, the rates of diagnosis and hospitalization occurred at 5 and 8 times, respectively, the rate of non-First Nations peoples (32). 15.6% have 3+ chronic conditions, more than double the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (7.6%), and this is especially the case for First Nations Australians living in remote areas (7). Additionally, many interventions put in place during the pandemic were counter-cultural or difficult to implement due to crowded housing and extended family networks living together. When combined with higher rates of housing insecurity, which is also associated with high rates of chronic disease and social disadvantage (33), this makes the risks all the more higher in a public health crisis.

In the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, until restrictions were lifted, First Nations peoples fared relatively well, with no deaths reported, largely due to a rapid community-led response aligning with government recommendations. Direct collaboration with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID‐19 in early March, 2020, proved crucial to the development of national guidelines tailored to First Nations communities (3,32). However, existing information does not specify the inclusion of homeless First Nations members. Overcrowded living conditions among First Nations peoples made isolation, vaccination, and treatment especially difficult, and response measures were not always tailored and culturally sensitive (3,7). A lack of aggregated data on homeless First Nations peoples makes estimating the true impact of COVID-19 on this community difficult and demonstrates the importance of intersectionality in data collection and pandemic response measures.

While many sources report on COVID-19 cases and responses within specific populations, few address the same topics across multiple populations, limiting opportunities for comparison. For example, statistics on cases and risk factors are available in regards to homeless Australians and First Nations peoples separately (3,7), but there is no reliable data on case prevalence amongst homeless First Nations peoples. Additionally, it is hard to find data based on homeless Australians and on CALD or First Nations peoples, similar in time frame and subject matter, hindering proper analysis and tailored solutions (7,10,34).

Xenophobia and Bias Towards Migrants, First Nations peoples, and Homeless Populations

Australia’s overall pandemic response was often colored by racial bias, with an especially significant impact on those experiencing homelessness. Governmental neglect and prejudice produce vulnerability at the social and economic levels, contributing to poorer health outcomes. Concerns were raised that state and territory enforcement of lockdown and other public health measures were over-policed or unfairly focused in areas with large minority or refugee populations, which are often associated with higher rates of housing insecurity (3). Such individuals may have reduced access to resources and often experience discrimination and social exclusion (35). For groups already facing animosity, such as migrants experiencing xenophobia, housing status can intensify prejudice and feelings of isolation (36). Negative experiences with culturally insensitive healthcare services may worsen barriers, access to and trust in healthcare (3).

Migrants face xenophobia and difficulties in accessing social services, issues which are tied to colonialism and continued patterns of inequality. This is only amplified in the face of public health crises. In 2022, 44.5% of all COVID-19 deaths in Australia were of those born overseas (3). The systemic exclusion of immigrant groups during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic invoked a racialized form of nationalism, legitimized by the conditions of the public health emergency. Migrants, specifically those from Asia, were often depicted as a health threat and economic burden through the media as well as through governmental policy, reinforcing sentiments of blame (23).

In 2020-21, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement erupted across the world, seeking to bring attention to the prevalence of racism in the criminal justice system (37). In 2021, First Nations peoples and supporters joined rallies in Australia’s cities. Despite claims of COVID-19 transmission links to BLM protests being refuted by Australian health officials, stigma characterizing the movement as criminally and socially irresponsible persisted, aligning with continued trends of racial polarization during the pandemic. Through agencies like Australian news groups communicating a linkage between protests and public housing, stigma and perceived risk were assigned to marginalized communities, largely CALD or First Nations Australians (23). In New South Wales, fines were ‘disproportionately issued to marginalised groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children’ (3,37). This legitimizes ideas of blame targeting the vulnerable, setting a dangerous precedent.

Inequities in Vaccination Services

Vaccination efforts are integral to combatting public health crises such as COVID-19. In Australia, there are significant disparities in vaccination rates, especially among different minority communities. Socioeconomically disadvantaged metropolitan areas had lower vaccination rates and took longer to reach vaccination goals, as was the case for Australians above the age of 16 with low English proficiency (3). There are many reasons for disparities in vaccine coverage among some such groups, including differing attitudes to vaccinations and levels of trust in the healthcare system. Bias and distrust of the system due to historical experiences of prejudice and denial of services produce fear surrounding accessing health services among groups like asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, homeless individuals, as well as those dealing with addiction. Factors such as language, cost, discrimination, or lack of culturally appropriate care create further barriers to proper healthcare, like delayed treatment and poorer health outcomes (4).

People experiencing homelessness face challenges with vaccination due to long-standing inequities in health and social stigma. For rough sleepers, access to healthcare is often jeopardized by mistrust of medical professionals, limited interaction with health care services, lack of transportation, frequent relocation, competing priorities such as finding food as well as shelter, and a scarcity of specialists educated on the needs of homeless individuals and how to sensitively and competently take care of them (4).

Homeless communities were frequently neglected by the government. The premature withdrawal of services included reduced efforts to promote the importance of COVID-19 boosters among this group, and decreased funding for services to access PPE, personal protective equipment (3,21). Vaccine communication campaigns were often too slow to communicate information and frequently ineffective, contributing to the spread of misinformation. Compared to 49% of all Australians, only 31% of First Nations peoples reported seeing vaccine campaign materials in December 2021. When community-led approaches were utilized and supported, recovery and vaccination initiatives were seen to be more successful in reducing case numbers and increasing vaccination rates (3). True engagement must be collaborative and not superficial.

Acknowledging Intersectionality in Advocacy Work

Advocacy must challenge structural racism and policy gaps that disproportionately affect many communities, such as visa restrictions, funding gaps, and mistrust. The marginalization and neglect of Australia’s vulnerable has further stigmatized these communities for their higher incidence of COVID-19 cases. In perpetuating patterns of systemic racism at all levels, Australia’s governments have undermined the health of these communities. This report has exemplified the intersections between those who are housing insecure, CALD, and First Nations. Many such individuals experience overlapping forms of disadvantage: compounded barriers inadequately addressed by single-issue advocacy.

Current support services are not intersectional, and in the COVID-19 pandemic, many were phased out before the end of lockdowns and the introduction of widely available vaccinations. Most homelessness services in Australia expanded or broadened over the pandemic, and many undertook a complete overhaul, but still did not address intersecting inequalities, increasing vulnerability to homelessness among many Australian populations. Testing, tracing, isolation and quarantine procedures during the transition/recovery phase were discarded and transferred from governments to community-controlled services without formal negotiation, placing members in a precarious situation that left individuals without proper assistance. Advocacy is needed for sustainable support during a public health crisis, responding to the long-term inequities through which many groups intersect, and must be phased out in a planned manner and in conjunction with service providers (3).

Many services, such as for homelessness, may not be culturally safe or linguistically accessible. Culturally competent education programs must be funded, implemented, and required for advocacy groups, healthcare providers, and key decision makers in government to counter prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to intersectionally appropriate care. This must be done in partnership with minority communities (4,30). The government must work with the public to build trust in vaccination and policy. Decision-making bodies must be more transparent in disclosing what underpins their decisions, and ensure channels are available for questions. The historical inadequacies of government-led efforts must be recognized, and those impacted must be treated and made to feel as a priority through inclusion. Research is needed into the origins of such disparities and the development of tools to reduce them, such as mandatory education. Input from and collaboration with experts must be embedded across all levels of government within Australia’s policies, working frameworks, and emergency planning (3).

Addressing the Problem: Targeted Solutions

Addressing the issues within the intersection of housing and minority status, and the resulting impacts on individuals’ health outcomes, requires targeted solutions. Underlying issues leading to housing precarity within differing minority groups must be addressed before the next emergency. Addressing intersectionality between minority groups and those facing homelessness requires more than a one-size-fit-all solution. This report has demonstrated the absence of an intersectional approach to addressing inequities and emerging crises, and that change is needed through comprehensive solutions.

Improvements to disaggregated data collection and linkage that is informed by local knowledge can help monitor the evolving needs of Australians. Comprehensive and quality data on minority groups must be part of existing routine collection systems, such as the Australian Immunisation Register, which does not collect data such as preferred language or country of birth. A formal means of accumulating data sources as a mechanism to inform policy and emergency responses must be designed, and this is particularly essential for Australians experiencing housing insecurity. A lack of robust and accessible data tracking the identities and backgrounds of those immunized or coming in and out of homelessness makes it difficult to assess the vulnerabilities of intersectional community members and develop tailored solutions. This is emblematic of the wider systemic health gap in Australia (3). Intersectional frameworks are needed to push for improved data that disaggregates based on ethnicity, cultural and linguistic backgrounds, hospitalization and mortality rates, and migration status. Timely data must be available to local and national care providers to inform actions and mitigate the disproportionate impacts of crises on minority communities. This will support evidence-based advocacy and help identify service gaps, emerging trends, and evaluations of the success of measures in ensuring the equitable access and uptake of services like vaccination (4,30,33).

To support vaccination efforts and prepare for health emergencies, the government must establish trusting relationships with communities that have faced disadvantage and marginalization throughout Australia’s history (9). Minority community members often prioritize social networks when seeking information, preferring to receive messaging from those like themselves. Research following the 2009 H1N1 influenza epidemic showed the unlikely effectiveness of one-size-fits-all approaches to infectious disease emergencies (32,38). Various studies have demonstrated that when responses were tailored to communities within health emergencies and immunization programs, they were more effective for the evolving needs of community members, as was seen in the First Nations-led response in 2009 (6). Organizations like Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services were key to developing local community responses and initiatives to lift vaccination rates. When flexible funding enabled services to create and spread appropriate public health messaging, better outcomes were seen. Increasing the representation of minorities among healthcare professionals and in leadership at all levels is a reachable goal (3,9,33).

Vaccination programs should be tailored to include decisive and sensitive outreach strategies to reduce barriers for those experiencing homelessness and for those who identify as CALD or First Nations. They must recognize the common intersections between these vulnerable communities, too often approached as separate. To support vaccination efforts, strategies focused on community collaboration, flexibility, people-centered and trauma-informed practice, and building networks of trust are essential (33). This can address vaccine hesitancy, communication gaps, and reduce barriers to care.

Future research and action will require a clearer understanding of the multiple and often interconnected dimensions of identity, and how it can impact individuals’ outcomes and treatment. Making people feel heard encourages trust, cooperation, and confidence in government and health experts. Intersectional solutions require policies and programs tailored to meet the diverse needs of individuals. To create long-term sustainable change, inequalities caused by wider social determinants of health, such as housing conditions, must be reduced through active efforts that are community-led and include collaboration across immigration, legal, and housing sectors.

References

1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Profile of Australia’s population. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/profile-of-australias-population

2. Abdi I, Gidding H, Leong RN, Moore HC, Seale H, Menzies R. Vaccine coverage in children born to migrant mothers in Australia: A population-based cohort study. Vaccine. 2021 Feb 5;39(6):984–93.

3. COVID-19 Response Inquiry Report. Barton, Australian Capital Territory: Commonwealth of Australia, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; 2024.

4. Chan J, Truong M. Diversity and COVID-19 vaccine rollout: we can’t fix what we can’t see [Internet]. InSight+. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Available from: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2021/5/diversity-and-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-we-cant-fix-what-we-cant-see/

5. Hengel B, Causer L, Matthews S, Smith K, Andrewartha K, Badman S, et al. A decentralised point-of-care testing model to address inequities in the COVID-19 response. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 July 1;21(7):e183–90.

6. Eades S, Eades F, McCaullay D, Nelson L, Phelan P, Stanley F. Australia’s First Nations’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2020 July 25;396(10246):237–8.

7. Yashadhana A, Pollard-Wharton N, Zwi AB, Biles B. Indigenous Australians at increased risk of COVID-19 due to existing health and socioeconomic inequities. Lancet Reg Health – West Pac [Internet]. 2020 Aug [cited 2025 Aug 19];1. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanwpc/article/PIIS2666-6065(20)30007-9/fulltext

8. Basseal JM, Bennett CM, Collignon P, Currie BJ, Durrheim DN, Leask J, et al. Key lessons from the COVID-19 public health response in Australia. Lancet Reg Health – West Pac [Internet]. 2023 Jan [cited 2025 Aug 19];30(100616). Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanwpc/article/PIIS2666-6065(22)00231-0/fulltext

9. Seale H, Harris-Roxas B, Heywood A, Abdi I, Mahimbo A, Chauhan A, et al. The role of community leaders and other information intermediaries during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from the multicultural sector in Australia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022 May 17;9(1):174.

10. Katikireddi SV, Lal S, Carrol ED, Niedzwiedz CL, Khunti K, Dundas R, et al. Unequal impact of the COVID-19 crisis on minority ethnic groups: a framework for understanding and addressing inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021 Oct 1;75(10):970–4.

11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Determinants of health for First Nations people. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/social-determinants-and-indigenous-health

12. Australian Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Estimating Homelessness: Census, 2021. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating-homelessness-census/latest-release

13. State of the Housing System 2024. Commonw Aust Natl Hous Affordabil Counc. 2024;

14. Herath S, Mansour A, Bentley R. Urban density, household overcrowding and the spread of COVID-19 in Australian cities. Health Place. 2024 Sept;89:103298.

15. UN-Habitat, editor. The value of sustainable urbanization. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat; 2020. 377 p. (World cities report).

16. Nicholas J. ‘Magnifying glass’ on inequality: why Covid is hitting harder in Melbourne’s disadvantaged areas | Victoria | The Guardian [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2021/sep/24/magnifying-glass-on-inequality-why-covid-is-hitting-harder-in-melbournes-disadvantaged-areas

17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Homelessness and homelessness services. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/homelessness-and-homelessness-services

18. National Rural Health Alliance. Social Determinants of Health in Rural Australia [Internet]. 2024 Nov [cited 2025 Aug 19]. (Fact Sheet). Available from: https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/NRHA-Social-Determinants-of-Health-Factsheet.pdf

19. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Rural and remote health. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health

20. Between 1.5 and 2 million Australian renters at-risk of homelessness: report | AHURI [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/analysis/news/between-15-and-2-million-australian-renters-risk-homelessness-report

21. Hartley C. Centre for Social Impact. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. The ongoing implications of COVID-19 for homelessness responses | CSI. Available from: https://www.csi.edu.au/news/the-ongoing-implications-of-covid-19-for-homelessness-responses/

22. McCosker LK, Ware RS, Maujean A, Simpson SJ, Downes MJ. Homeless Services in Australia: Perceptions of Homelessness Services Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Aust Soc Work. 2021 Aug 22;77(1):5–21.

23. Barber R, Law SF. Exposing Inequity in Australian Society: Are we all in it Together? Afr Saf Promot J Inj Violence Prev. 2020;18(2):96–115.

24. Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness, 2016 | Australian Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating-homelessness-census/2016

25. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Specialist homelessness services annual report 2020–21, Clients, services and outcomes. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-annual-report-2020-21/contents/clients-services-and-outcomes

26. Abdi I, Tinessia A, Mahimbo A, Sheel M, Leask J. Is it time to retire the label “CALD” in public health research and practice? Med J Aust. 2025 Mar 17;222(5):220–2.

27. Freund M, Clapham M, Ooi JY, Adamson D, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher R. The health and wellbeing of Australian social housing tenants compared to people living in other types of housing. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Nov 24 [cited 2025 Aug 19];23(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17267-2

28. Ioannides S J, Hess I, Lamberton C, Luisi B, Gupta L. Engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse communities during a COVID-19 outbreak: a NSW Health interagency public health campaign – September 2023, Volume 33, Issue 3 | PHRP [Internet]. https://www.phrp.com.au/. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.phrp.com.au/issues/september-2023-volume-33-issue-3/engaging-cald-communities-with-covid-19-campaign/

29. Davey M, Nicholas J. Covid death rate three times higher among migrants than those born in Australia. The Guardian [Internet]. 2022 Feb 17 [cited 2025 Aug 19]; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/feb/17/covid-death-rate-three-times-higher-among-migrants-than-those-born-in-australia

30. Razai MS, Kankam HKN, Majeed A, Esmail A, Williams DR. Mitigating ethnic disparities in covid-19 and beyond. BMJ. 2021 Jan 15;372:m4921.

31. Curtice K, Choo E. Indigenous populations: left behind in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet. 2020 June;395:1753.

32. Crooks K, Casey D, Ward JS. First Nations peoples leading the way in COVID‐19 pandemic planning, response and management. Med J Aust. 2020 July 20;213(4):151–2.

33. Hollingdrake O, Grech E, Papas L, Currie J. Implementing a COVID-19 vaccination outreach service for people experiencing homelessness. Health Promot J Austr. 2025;36(1):e885.

34. Kapilashrami A, Hankivsky O. Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. The Lancet. 2018 June 30;391(10140):2589–91.

35. Blackford K, Crawford G, McCausland K, Zhao Y. Describing homelessness risk among people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Western Australia: A cluster analysis approach. Health Promot J Austr. 2023 Oct 2;34(4):953–62.

36. Fredericks B, Bradfield A, Ward J, McAvoy S, Spierings S, Toth-Peter A, et al. Mapping pandemic responses in urban Indigenous Australia: Reflections on systems thinking and pandemic preparedness. Aust N Z J Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Aug 19];47(5). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1326020023052615

37. Why does the BLM movement matter in Australia? [Internet]. United Nations Association fo Australia (UNAA). 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.unaa.org.au/2021/11/03/why-does-the-blm-movement-matter-in-australia/

38. Massey PD, Miller A, Durrheim DN, Speare R, Saggers S, Eastwood K. Pandemic influenza containment and the cultural and social context of Indigenous communities. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(1):1179.